Except for a short sojourn in Purley (sort of south London) I have lived in the countryside all of my life – either in Wiltshire or the four years I spent in rural France. Consequently, my immediate response to this week’s prompt is how much my ancestors would have watched the land around them change.

Not only the land, of course, but their villages changing as shops closed, services withdrawn and then acres of post-war housing and, of course, the rise of the motorcar and the roads they ran on. Now, some of those changes are still being faced by rural communities today.

(It’s telling that I just googled “countryside” and the first result is a building developer specialising in “communities” of soulless new-build houses.)

Of course, what is easy to forget is that what we see as “unspoiled” countryside is in fact, nothing of the sort, but reflects centuries of man altering the landscape and environment to suit itself, right from Bronze and Iron Age tree-felling across valleys and hilltops (the Wessex Chalk Downlands were cleared of secondary woodland by the Middle Bronze Age to enable arable farming, for example) to the Saxon open-field farming systems. However, it would be disingenuous for me to imply I have an identifiable Bronze Age ancestor!

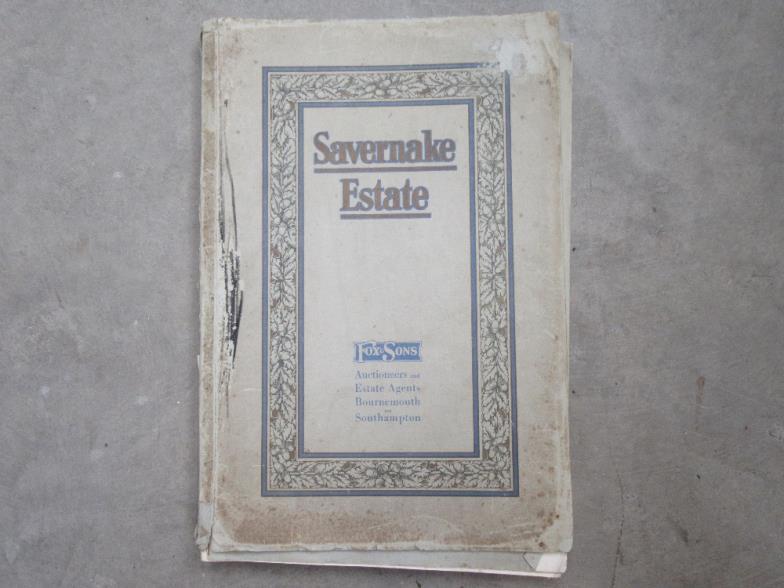

What we call the British countryside and what we would recognise as a system of fields bounded by hedgerows didn’t come into effect until the 18th and 19th centuries and the practice of Enclosure which removed the open-field system. In Collingbourne Kingston, the ancestral parish of my father’s maternal family, all land, including previously common pasturage was inclosed by 1824, and most of the land concentrated in 2 farms owned by the Savernake Estate and the Marquess of Ailesbury until 1929 when most of the estate (25,000 acres, with 16,000 acres being retained) was auctioned off into private hands. But more on that later …

However, the largest change they would have witnessed was the huge population decreases.

The decline in population for most rural parishes had begun in the mid-nineteenth century and continued, for most of them, until the 1960s when greater car ownership meant that people could commute to work from villages. There were several reasons for this including;

- Various agricultural depressions of the later 19th century

- Better paid industrial employment in local towns; for north east Wiltshire this would have been the Great Western Railway Works at Swindon. During the First World War they and other industries in Swindon carried out war work requiring both men and women who would have moved into the town from elsewhere.

- The era of ‘high farming’ more or less ended by the second decade of the 20th century and fewer men were required on the farms

- Comparatively large numbers of young men from the villages were killed in the First World War; in farming terms these were the breeding stock that would have produced the next generation of young villagers. Without them many village girls would have looked to, and moved to, the towns to find husbands.

- There was a decline in village shops and trades between the wars although this was not too apparent until after the Second World War.

- With improved education many village men were not content to earn low wages as farm labourers but sought other jobs in the towns

- The agricultural depression of the late 1920s and 1930s meant that many farms, particularly arable farms, laid off men and continued with a minimum of labour. The (Collingbourne) invention of the Hosier bale milking system and the increase in egg production over other types of farming enabled farms to continue with fewer men. Those that did not adapt often became untenanted and derelict.

- The increasing use of the internal combustion engine did change jobs. For example, blacksmiths took to straightening out dented vehicles and some became garage owners; decreasing use of horses on the land meant fewer farriers, lorries replaced the carrier’s cart, and shops in the towns found it easier to send representatives to sell their wares in villages and maybe caused a village shop or dressmaker to close.

- Some men returning from the war may have found their village too small; until the war they may rarely have gone further than the local market town with an occasional charabanc trip to the seaside. Now they wanted to take opportunities that the village could not provide.

Large estates selling off land after World War I was not uncommon. The Longleat Estate sold over 8,600 acres between 1919 and 1921, and the Astley Baronets sold off 4,500 acres of their Everleigh estate in 1917. The Savernake Estate was first sold in January 1929 and amounted to 25,000 acres (around 40 square miles) out of the 41,000 acres being sold to a Mr E C Fairweather for around £250,000 (around £16 million in today’s money). He resold it to financier and stockbroker Sir Arthur Wheeler, who then put it up for public auction in September 1929. For the eight villages the estate covered, this would have been a huge life-altering event, with some tenants facing the prospect of becoming landholders.

Of course, this was more successful for some than others. (As an aside, Sir Arthur Wheeler later died penniless in 1943 but not before he had managed to also purchase Sir Joseph Beecham’s London estate which included Covent Garden, London Opera House and Covent Garden Market.) The Hosier family of Collingbourne Kingston became one of the principal landholders in the village and owned Aughton House Farm and Brunton Farm. The May family were the other, owning Manor Farm (later split into two to include Summerdown Farm) and then Mr Crook who later purchased Parsonage Farm. Of course, they also held land in neighbouring parishes. These families remain the primary farmers in the village today. Of course, they also became the proprietors of large numbers of workers cottages. For the majority of inhabitants who couldn’t afford to buy, they simply swapped one landlord for another.

For all its faults, Wikipedia has a rather good entry around the destruction of country houses in 20th century Britain and goes in to some detail around why estates were broken up and sold off.

I do wonder what those oldtimers would make of modern rural life today. From modern farming techniques to land use to the disappearance of old water courses, woodlands and common ground to the invasion of post-war buildings and the dereliction of many village centres. Thankfully the good old-fashioned familiarity of crushing rural poverty still remains.

Cover image: Ian Redding Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto