In my musings, I very often neglect the tales of my father’s English family, especially those of his maternal grandfather. For this reason, I’ve been taking another look at the early Murray families to see what new information I can uncover.

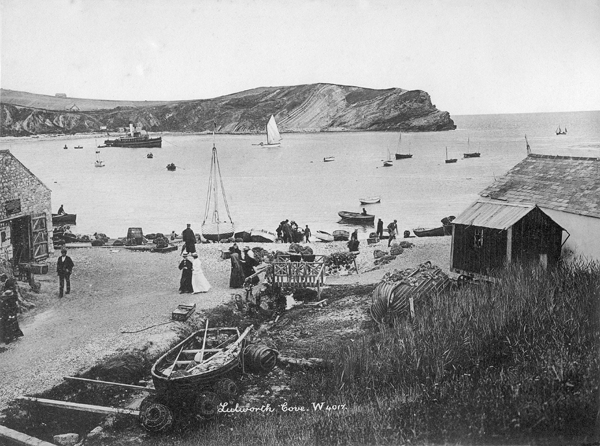

I was absolutely thrilled to find out that the Murray family research lead me down to the south coast of Dorset and the Jurassic Coast of Lulworth Bay. It was one of my favourite places to go as a child, along with Swanage, Kimmeridge Bay, Durdle Door, and the like. It is a stunning place to visit. Less so for the poor residents of West Lulworth who are often faced with a surfeit of tourists during the summer. But that’s a whole different issue and was being complained about in the early 1900s – confirming the adage that there really is nothing new under the sun!

The very first mention of the Murrays in and around Lulworth is the baptism of my 4 x great-grandfather, Thomas, in 1779. His parents were John and Mary. John died in 1813, and Mary in 1783 – she died shortly after the birth of their youngest child, Ann, who was buried on 30 April, about a month after her baptism on 28 March. Mary was buried on 28 April. This left John with two boys to raise on his own. Surprisingly, he didn’t seem to remarry. John’s stated age at death implies a year of birth c. 1756. West Lulworth parish registers survive from 1745 and are pretty complete after that date. However, neither his baptism nor his marriage to Mary is recorded. Neither do they appear in East Lulworth, nor in the surrounding parishes. Where they were from before this seems to remain a mystery for now.

I suppose that now is as good a time as any to mention spellings. I’ve touched on it before, but there is a surprising array of spelling variants in the parish records for Murray. I suppose partly due to the thick Dorset accent. It can be Murray, Murry or Mury, or Morey, or Murrey. It also seems to go in swathes (ie whoever was recording was consistent for as long as they were the one recording it) and then a new variant would present itself, or a neighbouring parish would spell it differently for their marriage, etc. I touch on this a little in my blog about my Murray great-grandfather, Jesse.

This is also an instance where other people’s trees with those shaky, shaky leaves are of no use. A large number of them have John being born in Scotland and marrying a Mary Stamp (where they haven’t confused his marriage with that of his son, also called John, who also married a Mary in 1803) who somehow had children in Northumberland (very north of England), Kentucky (USA), and Lulworth (very south of England) before dying in Virginia (USA), possibly before she gave birth to her youngest children. Yep, you read that right. Was there a John Murray baptised in Scotland c. 1756? Yes, several in fact. Did one marry a Mary Stamp? Yes. Do I think these are my ancestors? I’m not saying it’s impossible, but I am saying it’s highly unlikely.

Another surprise was finding out that the vast majority of the family had nothing to do with the sea, but were farmers. I mean, even coastal communities need things like bread and vegetables. There was a Joseph Murray, a cousin of my 3 x great-grandfather, Edward, who became a shipwright in Poole. However, he seems to be almost the only one.

And talking of surprising occupations, I found a very interesting string of Murrays …

My 5 x great-grandparents – John and Mary – had at least three children: Thomas, John and Ann. We have already seen that Ann sadly died when she was only a few months old, along with her mother, Mary. I am descended from the eldest son, Thomas, who married twice and had seven children. John (junior) also had seven children with his wife, Mary Snelling. This family seems to have left Lulworth and moved to the neighbouring parish of Tyneham. (As an aside: Tyneham is now a ghost village. In 1943 the Ministry of Defence requisitioned the village and 30km2 of surrounding land as firing ranges and for training troops. What was supposed to have been temporary all changed in 1945 when the MoD applied a compulsory purchase order to the site. It is still used as a firing range today, although the area is open to the public in August and on Sundays.)

- Harriot b. 1803 East Lulworth, married 1821 in Tyneham, d. 1887 Tyneham

- George b. 1806 Tyneham, married 1850 in Southampton, d. 1872 Ryde, Isle of Wight

- Benjamin b. 1810 East Lulworth, married 1831 in London, d. 1865 Hartlepool

- Joseph b. 1811 Tyneham, married 1835 Poole, d. 1895 Portsea

- John b. 1816 Tyneham, married 1841 Brimpton, Berkshire – entire family of 4 disappear after 1851 census

- Samuel b. 1819 Tyneham, married 1851 in Tyneham, d. 1908 Tyneham

- Mary Anne b. 1821 Tyneham, d. 1828 East Lulworth

As you can see above, most of the children stay in Dorset, marrying local families. One made it all the way to the Isle of Wight, and one to Portsmouth (well, Portsea, but close enough). One disappeared altogether after 1851. John was a gamekeeper so theoretically it was an occupation that could travel to any point in rural England, Scotland or Wales. I’m sure he’ll come to light at some point in the future, but that left one other child who didn’t stick to his Dorset homeland: Benjamin.

I found a reference to a Benjamin Murray born in Povington, Dorset, living in Stranton, County Durham (now part of West Hartlepool) in the 1861 census, with his wife Mary. It struck me as some of his siblings had also listed their place of birth as Povington in census returns, and historically this was a small hamlet surrounding a farm just to the north of Tyneham.

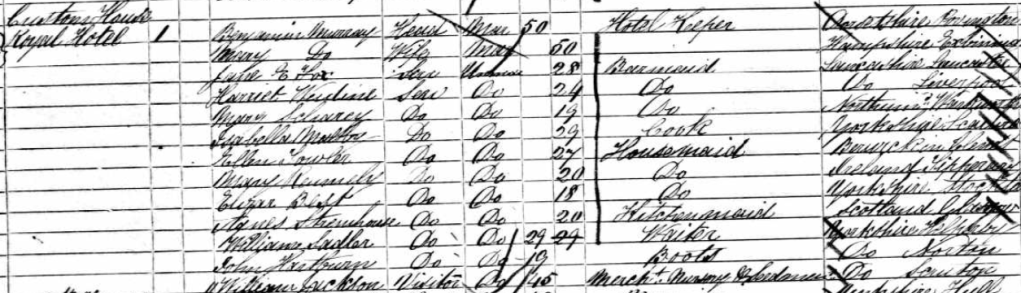

Now very little remains of the houses there, and the name only survives in Povington Hill, one of the highest points of the Purbeck Hills. The whole area around Tyneham is off-limits due to MOD training, although some areas are open at weekends (not Povington, however). So I had a good reason to think this was my missing Benjamin. He was listed as a hotel keeper at the Royal Hotel on Church Street.

But what had happened to him between his baptism in 1810 and his appearance in 1861? The 1851 census added a few clues to the picture …

Here, he is living in Norton, County Durham (a town in Stockton-on-Tees), about 10 miles to the south of Hartlepool. In the household are his wife, Mary, and two children “Robert” (more on him later) and Emily. Although his place of birth is listed as Southampton, his wife is listed as being born in Wareham, Dorset. Which is a bit of a coincidence as Wareham is the name of the Registration District that covers East Lulworth, Tyneham and Povington. The children are born in London and “Mask” in Yorkshire (which must be a misspelling of Marske). But the clincher was the fact that Benjamin’s occupation is “insolvent innkeeper”. Which made my little heart sing because insolvency would have been covered by his local press. And who doesn’t love a trawl through the newspapers?! Extra bonus points for one of the children being born after civil registration, meaning that their birth registration would show the mother’s maiden name, making finding Benjamin and Mary’s marriage easier.

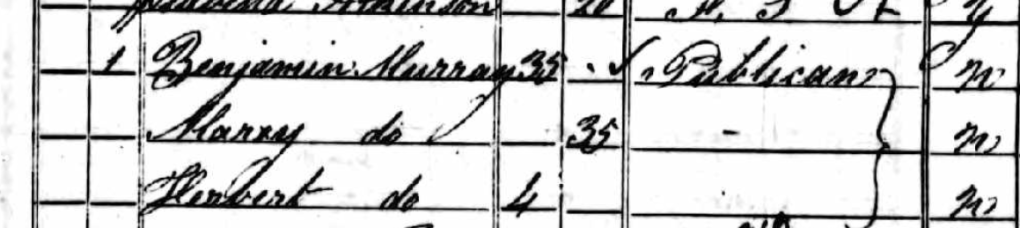

Moving back another 10 years, I was able to find a likely Benjamin, Mary and their son living on High Street, Stockton, County Durham. Benjamin is listed as a Publican, and none are born in the county.

Historically, hotels and inns – especially coaching inns – were incredibly important for the economies of the towns and villages in which they were situated, and acted as community gathering places as well as providing food and lodging for travellers. Coaching inns had the extra component of providing replacement horses for the coaches that stopped there. Along with the horses, it was not unusual for larger coaching inns to also provide extra tack and also provide repair facilities for hire (nothing comes for free!). This came to higher importance on the Royal Mail delivery routes where speed was of the essence and fines were levied against delays (I could say something pithy about modern delivery/courier companies, but that would take too long!).

A lot of the coaching inns on arterial routes died a death when the railways arrived, but on other routes they survived and saw a resurgence with the arrival of the personal automobile and increased leisure time for trippers. However, their community aspect never quite recovered. Historically, sales and auctions would take place in the local inn, as well as coroner inquests and legal proceedings that were not presented at the quarterly assize courts.

Therefore the innkeeper was often a key member of the local community. And it is in the announcements of local activities that we find our first mention of Benjamin Murray. In July 1841 he is noted as providing dinner to The Stockton and London Shipping Company’s General Annual meeting at the Black Lion in Stockton. The previous hotel landlord, Mr Ludley, is mentioned in an article about the annual tea festival of the Stockton Mechanics’ Institution in January 1841. One assumes he sold the hotel in time for Benjamin to have moved there by the time of the census in June 1841.

Benjamin continues to be mentioned as hosting local sales and auctions at the Black Lion until 1850 (in 1843 and 1844 he is noted to have taken over the Cock Inn, once the largest inn in Guisborough, “for the term of years”. He is listed as also being of the Black Lion, Stockton. A vellum conveyancing document is in the local museum dated to July 1846 which perhaps links with his leaving. However, details of the document are difficult to find and so far I haven’t had any response to my query regarding any names mentioned.

As to his financial difficulties, the first appearance that something is awry is from September 1850 in the Durahm County Advertiser:

The fact he is selling “for ready money” implies that he needs the cash. Later that month, Benjamin appears at the Stockton Petty Sessions for non-payment of church rate. (This was a tax levied in parishes for the upkeep of the church. Interestingly, this tax was covered only by ‘Common Law’ and had no legal validity – it was abolished by statute in 1868.)

Only a couple of weeks later, a “Petition for an Adjudication of Bankruptcy” was filed in Newcastle upon Tyne. Benjamin is listed as an “Innkeeper, Wine & Spirit Merchant, Dealer in Roman Cement [a kind of ‘natural’ cement formed by the burning of certain types of carbon-rich deposits found in clay deposits], and Farmer” and was instructed to attend the first sitting in November 1850. Various subsequent sittings were required from Benjamin and his creditors. One such sitting was reported in from February 1851 and contained what some would call ‘an amusing bit of badinage’ as well as some additional information on Benjamin and his character.

It seems he saw he was getting into trouble in 1844, which then worsened to the point that he gave up the Black Lion in Stockton and took over another presmises in Stockton known as “the Town Hall Inn” – I believe this was also known as the Crown & Anchor which was later vacated by the middle of the 19th century and a namesake pub exists close to the site today in Stockton. Benjamin (or at least “it was stated in some quarters”) gave the exucse that the development of nearby Hartlepool Docks had damaged the trade in Stockton. His solicitor declined to comment on the veracity of that claim.

I think it speaks well of him that the court agreed that he had “acted honourably” when attempting to sort his debts privately, despite it being “clear Murray ought to have been bankrupt in 1849”

He was granted a certificate of the second class. A Second-Class Certificate was awarded to a person who had previous insolvencies, had attributed to the insolvency due to incorrect supervision or incorrect accounting, but had tendered a full disclosure to the court.

(As for the amusing part – I guess when you’re an insolvency solicitor, you take your laughs where and when you can get them!)

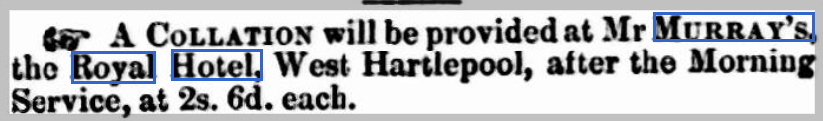

Apart from the 1851 census, the next time we hear from Benjamin is an advert in April 1854:

In this context, a “collation” is a light, informal meal where people serve themselves, probably what we would nowadays call a buffet.

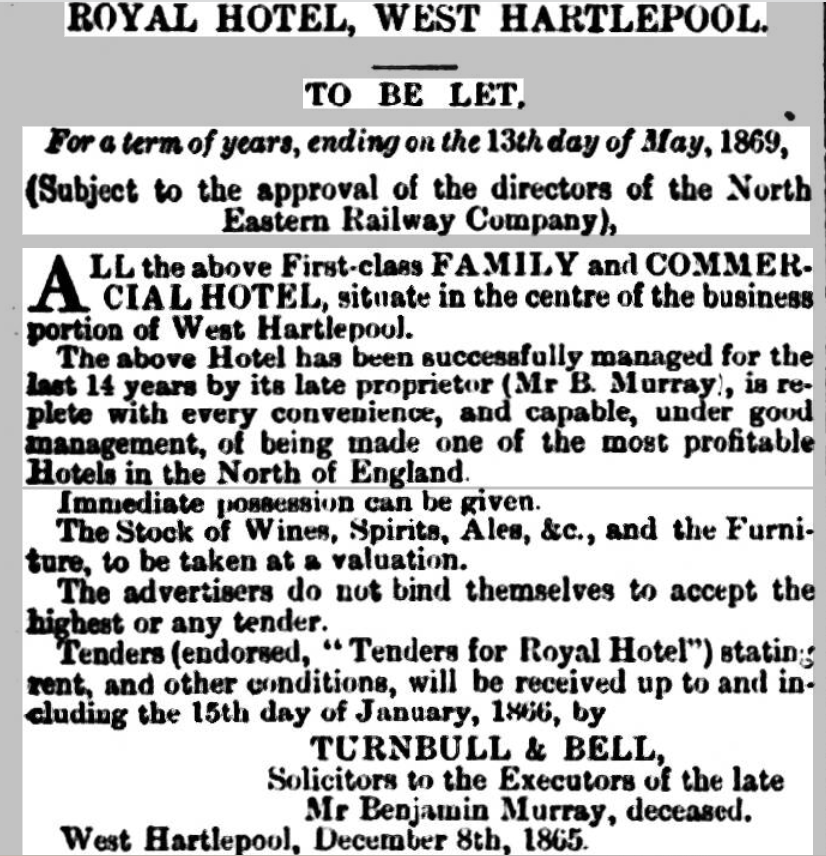

Benjamin disappears for a time, but appears again as innkeeper of the Royal Hotel, Stanton from early in 1854. It is there we find him in 1861, and it is there he remains until his death in December 1865 of chronic hepatitis and anasarca (swelling of the whole body due to fluid retention in subcutaneous tissue). After his probate was settled on 9 December 1865, the property’s lease was advertised:

Benjamin’s will doesn’t give any great information, only that he left everything to his wife, Mary, and his son and son-in-law were the executors.

I will be back with more on Benjamin’s marriage and his children in due course, but for now I feel a trip to the pub coming on – purely to support all our modern innkeepers in memory of Benjamin!

Cheers!